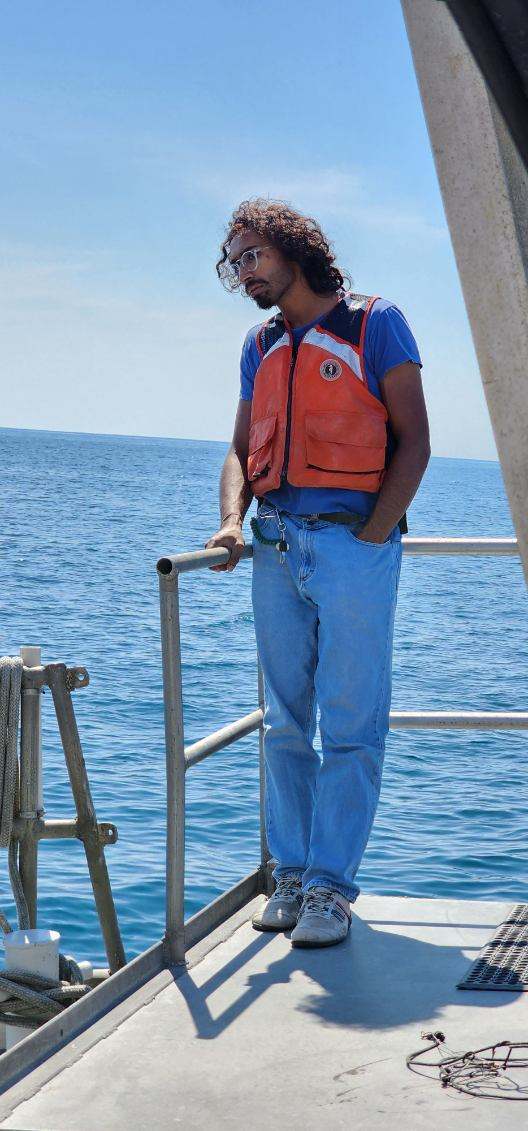

N 36 degrees 59.562 W 075 degrees 24.337 roughly 30 miles off the coast of the Virginia-Carolina border aboard the Virginia Institute of Marine Science Research Vessel:

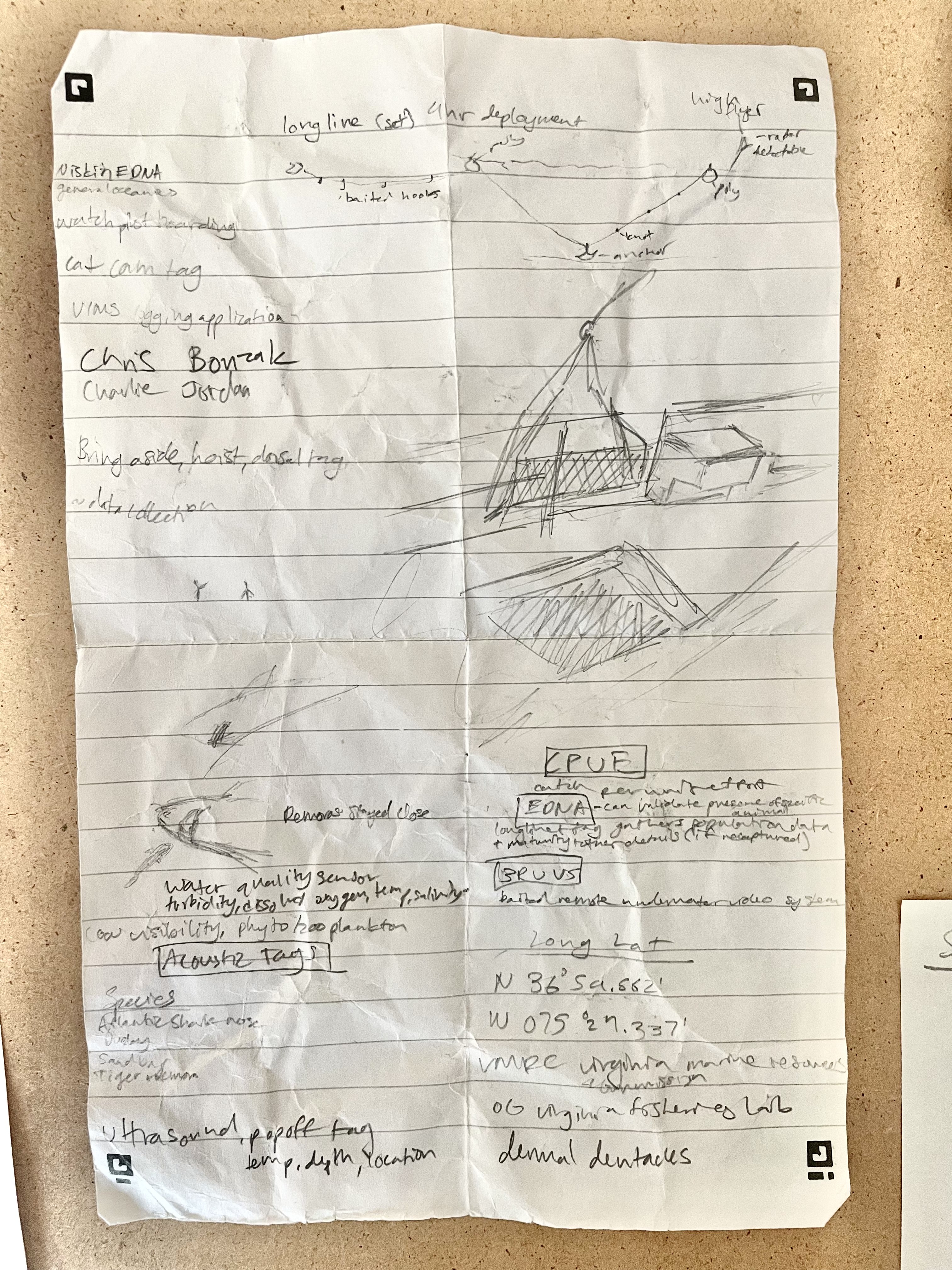

I peered over the edge of the railing at a several hundred pound Tiger shark we'd hooked. I'd expected to feel excitement, fear paired with adrenaline, but instead I just felt sad. The Tiger was almost catatonic. It floated on its back as the two Remoras it traveled with swam in circles nearby. It hadn't been a fair fight. In fact we'd totally missed the fight. The shark was caught on one of a hundred hooks we'd set out 4 hours prior-we were just now circling back.

One year prior, Paul Clerkin and Miguel Montalvo walked into the Robotics club at William and Mary. I ran the club, and they explained that they wanted something that would streamline the process of tracking marine animals. The current practice of hooking the beast, pulling it on board and then piercing its dorsal fin to tie a tag through was barbaric and outdated. Solution? A non-invasive clip-on shark tag. I was excited, and I got to work. In fact the first time I dropped out of college I was heads down building this tag. But now, on the boat, seeing the process I was getting involved with, I didn't find myself so motivated. This was the beginning of the end of my Marine robotics arc.

I went back to Williamsburg and I wanted to give it another shot. I had built up experience and connections for a potential career as a marine robotics guy. I wanted to know if I could be involved with marine science out of my own love for it. So I rode Ginger's bicycle down to lake Matoaka. I found a secluded spot off the trail and took off most of my clothes. I slowly stepped into the frigid water and tip toed forwards until I was submerged. My feet sunk into the mass of leaves that had settled and begun to decompose on the lake floor. Now with my head submerged I tried to find some personal connection to the lake. Any semblence of love or emotion that could justify my working towards marine robotics. I got out of the water and put my clothes back on. The water was freezing. A week later I spoke with a faculty member who headed research on water quality and the Lake. He told me there were massive alligator Gar in the lake. I didn't care about the lake anymore. It was over, I'd have to find something new.

As a student and as an engineer, I've often been told to forgo the white rabbit in favor of being practical. Its true-it is a tricky dance to entertain your curiosity. The answers you hope for rarely come. Rather, the questions keep evolving. But when you finally sit with your work and reflect, it becomes obvious that the winding path was the straightest possible one.

In my Religious Studies classes I explored Consciousness through multiple philosophical frameworks. In my Computer Science classes I delved into the algorithms foundational to neural networks. At some point early last year, there was much talk of AGI becoming "Conscious". These conversations even made it to the dinner table at Thanksgiving. Suddenly, my seemingly isolated coursework had a clear overlap. I was gripped by this intersection. Could AI become "Conscious"?

In Computer Science, a crucial concept is Abstraction. Tidy up the details of implementation and expose only a stable interface. This is necessary for building adaptable and complex systems. But to answer the question: could AI be conscious required diving deep.

I started by learning C and studying RISC architecture. I read datasheets and wrote firmware for ARM processors so I could directly interface with memory and create a Perceptron. Still, I didn't find any answers about how AI could become "Conscious". So I went deeper. I bought physics textbooks and snuck into Physics classes. I studied Maxwell's equations, Feynman's lectures and Einstein's Relativity. I could calculate field strength at a point, appreciate the elegance of the equations and make use of the water analogy but I still lacked a felt understanding. If electrical signals could somehow make AI "Conscious", I knew I had to build an intuition. So I designed an instrument. I wanted to hear, feel and see electricity.

Below is that instrument and a snippet of sound I just recorded. I found my answers. I've found more questions.

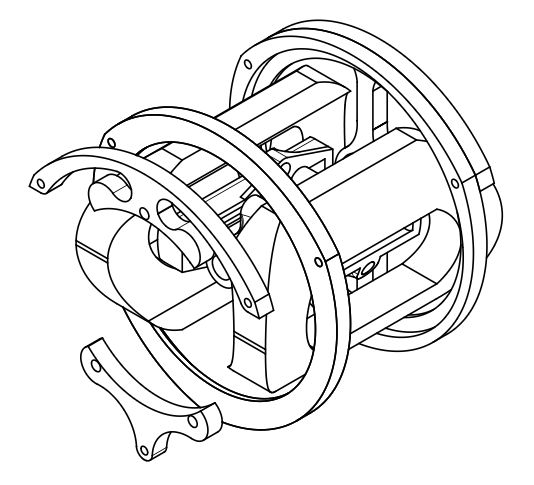

The bell and stator are from a brass AC motor used in old Naval vessels. The shaft and gearbox are from a 70's Craftsman drill, back when solid metal gears were used. The crank is from an old Phonograph. Various components are milled from 1/4" aluminum and held together with aluminum standoffs. The rotor is a 3D printed springloaded design to allow for fine tuning the air-gap and swapping out magnet configurations.